By: Gwen Miner, Supervisor of Domestic Arts

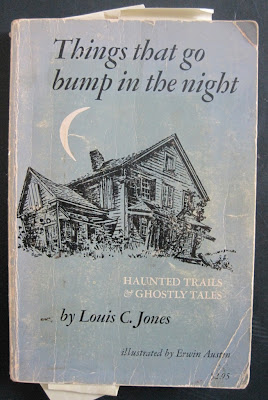

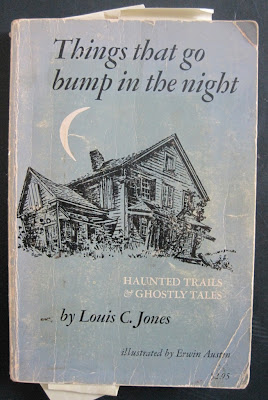

If you’re into ghosts, ghostly tales and hauntings, you really should pick up a copy of

Things That Go Bump in the Night by Louis C. Jones. I bought my copy many years ago, when I first started working here at the museum. The pages of the book are now yellowed with age and dog eared, but every year at this time I pull it out to re-read various parts for a new ghostly tale to tell on our

Things That Go Bump in the Night Tours here at the museum.

I remember first reading the book alone in my apartment. It was the first adult ghost story book I had read. Not a good idea to read ghostly tales at night when you live alone in a creaky old house. So believable were the tales in the book to me at that time, I thought ghosts might lurk around every corner. Maybe the tales were more believable, because they took place here in New York State and near to where I grew up.

The book is about stories of ghosts and hauntings that have been kept alive by the retelling of the stories from one generation to the next. Dr. Jones and his students in Eng. 40: American Folklore in the early 1940s spread a “dragnet” across New York State, bringing in “child lore, proverbs, songs, tall tales, short tales, legends, and especially the tales of the supernatural”. Dr. Jones was always intrigued by ghosts, witches, and the Devil and his followers. His folklore archives are rich in the supernatural genre. Only a fifth of the stories that were collected during his six years teaching this class are told in this book. The tales that were collected, and not published, remain safe and sound and available to the interested at the library at the New York State Historical Association.

This is the 50th anniversary of the book and to me it is a classic that anyone interested in ghosts and ghostly tales should have. To quote Dr. Jones in his preface, “…I think we came up with a clear picture of what our countrymen say about the restless dead, a subject that has been of human concern since the first flame flickered in a cave, since men learned to love and face death.” Believe me when I say I have read a lot of books on ghosts the last few years, but Things That go Bump in the Night remains my favorite, because the tales are told in story form and not an accounting of an event.

The book was also my inspiration – along with ghostly happenings that have reportedly occurred here at The Farmers’ Museum – five years ago to develop the Things That Go Bump in the Night Tours here at the museum. After all, Dr. Jones was our first director and he did write the book here in Cooperstown.

The following is Susan Fenimore Cooper’s observation of a New Year’s Day in Cooperstown in the late 1840’s from her book Rural Hours:

The following is Susan Fenimore Cooper’s observation of a New Year’s Day in Cooperstown in the late 1840’s from her book Rural Hours:

The American New Year’s cake originated in the New York. New Year’s cake was white and often contained caraway cakes and was made plain or cut in rounds or squares like the recipe in Amelia Simmon’s American Cookery of 1796. It could also be ornamented with cake “prints”. The smallest molds were used in the home for koekje (“little cakes”), from which or present-day term cookie is derived. The custom of making these cakes came to New York in the 17th century with the Dutch and was gradually passed on to their English neighbors.

The American New Year’s cake originated in the New York. New Year’s cake was white and often contained caraway cakes and was made plain or cut in rounds or squares like the recipe in Amelia Simmon’s American Cookery of 1796. It could also be ornamented with cake “prints”. The smallest molds were used in the home for koekje (“little cakes”), from which or present-day term cookie is derived. The custom of making these cakes came to New York in the 17th century with the Dutch and was gradually passed on to their English neighbors.

Most homes in the 19th century had cellars under the house for preserving vegetables. Climate-wise cellars were cool and moist, the ideal environment for cabbage, apples and most root crops. For those who did not have large enough cellars (or no cellar at all), certain vegetables were overwintered in the garden in straw lined trenches or hills that were covered over with more straw and soil.

Most homes in the 19th century had cellars under the house for preserving vegetables. Climate-wise cellars were cool and moist, the ideal environment for cabbage, apples and most root crops. For those who did not have large enough cellars (or no cellar at all), certain vegetables were overwintered in the garden in straw lined trenches or hills that were covered over with more straw and soil.  When the vegetables are dry enough they are carried to the cellar for winter storage. In the Lippitt Farmhouse cellar we use large footed wooden bins with wire tops to store our root crops, barrels for apples and we hang the cabbages by their roots.

When the vegetables are dry enough they are carried to the cellar for winter storage. In the Lippitt Farmhouse cellar we use large footed wooden bins with wire tops to store our root crops, barrels for apples and we hang the cabbages by their roots.  The productive root cellar is one that is well tended. It’s important to cook the soft vegetables, throw away the rotten ones and keep rodents away.

The productive root cellar is one that is well tended. It’s important to cook the soft vegetables, throw away the rotten ones and keep rodents away.  About a week ago we harvested

About a week ago we harvested  Root crops were the primary vegetable foodstuffs grown for much of the 19th century due to the available technology for the long term preservation of foodstuffs. A permanent method of freezing was not available and home canning did not become a common method of food preservation until the latter part of the 19th century. What couldn’t be put down in the cellar was “put up,” hung up to dry. All you would have needed was the correct environment and the “know how” for the successful storage of most of the vegetables grown in the 19th century.

Root crops were the primary vegetable foodstuffs grown for much of the 19th century due to the available technology for the long term preservation of foodstuffs. A permanent method of freezing was not available and home canning did not become a common method of food preservation until the latter part of the 19th century. What couldn’t be put down in the cellar was “put up,” hung up to dry. All you would have needed was the correct environment and the “know how” for the successful storage of most of the vegetables grown in the 19th century.  Harvesting this year was easy. I hate to say it, but it only took a few hours to bring all the vegetables in. It was not a good growing year. The vegetable yield this year was only a fraction of what we normally grow in a good year. The vegetables overall were in good condition but in size they were small to the occasional large.

Harvesting this year was easy. I hate to say it, but it only took a few hours to bring all the vegetables in. It was not a good growing year. The vegetable yield this year was only a fraction of what we normally grow in a good year. The vegetables overall were in good condition but in size they were small to the occasional large.  I remember first reading the book alone in my apartment. It was the first adult ghost story book I had read. Not a good idea to read ghostly tales at night when you live alone in a creaky old house. So believable were the tales in the book to me at that time, I thought ghosts might lurk around every corner. Maybe the tales were more believable, because they took place here in New York State and near to where I grew up.

I remember first reading the book alone in my apartment. It was the first adult ghost story book I had read. Not a good idea to read ghostly tales at night when you live alone in a creaky old house. So believable were the tales in the book to me at that time, I thought ghosts might lurk around every corner. Maybe the tales were more believable, because they took place here in New York State and near to where I grew up.

Even as a staff member who knows the grounds well, I was affected by the museum’s atmosphere at night (and I’ll admit that I was jumpy even though I knew that tricks and surprises were not part of the tour). If you want to take the tour, check out

Even as a staff member who knows the grounds well, I was affected by the museum’s atmosphere at night (and I’ll admit that I was jumpy even though I knew that tricks and surprises were not part of the tour). If you want to take the tour, check out

Congratulations to this year’s group of Young Interpreters! On Thursday, September 17, we held the annual Young Interpreter potluck dinner in Bump Tavern. This dinner concludes the summer-long program for the Young Interpreters. Nine of the eleven participants were present. The Young Interpreters and their immediate families join their mentors for a meal, conversation, a show and tell of the Interpreters’ summer work, and the presentation of certificates.

Congratulations to this year’s group of Young Interpreters! On Thursday, September 17, we held the annual Young Interpreter potluck dinner in Bump Tavern. This dinner concludes the summer-long program for the Young Interpreters. Nine of the eleven participants were present. The Young Interpreters and their immediate families join their mentors for a meal, conversation, a show and tell of the Interpreters’ summer work, and the presentation of certificates.

We hope to continue to see these fantastic young folks as volunteers and even future staff members.

We hope to continue to see these fantastic young folks as volunteers and even future staff members. The five beds in Lippit Garden Our Kitchen Garden at the Lippitt Farmhouse is laid out as a garden would have been for much of the nineteenth century: geometrically in beds. The garden consists of five beds. Three of the five as of this writing are slowly growing. Two, because they were either under water or wet most of the summer were a lost cause by July. At this point we are harvesting potatoes, turnips and early cabbage for use, but is looking like we won’t have much to “put down“ in the cellar for winter use. For the most part though, the development of the vegetables is where they would be the end of July or early August even though it’s already mid-September.

The five beds in Lippit Garden Our Kitchen Garden at the Lippitt Farmhouse is laid out as a garden would have been for much of the nineteenth century: geometrically in beds. The garden consists of five beds. Three of the five as of this writing are slowly growing. Two, because they were either under water or wet most of the summer were a lost cause by July. At this point we are harvesting potatoes, turnips and early cabbage for use, but is looking like we won’t have much to “put down“ in the cellar for winter use. For the most part though, the development of the vegetables is where they would be the end of July or early August even though it’s already mid-September. A bed with growing plants.

A bed with growing plants.  A bed that is too wet.

A bed that is too wet.  Small turnips Lessons from this cold, wet summer:

Small turnips Lessons from this cold, wet summer:

Do you have an old smokehouse on your property? We want to know about it. Leave us a comment so we can add it to our list.

Do you have an old smokehouse on your property? We want to know about it. Leave us a comment so we can add it to our list.

Second, we put the frame together on top of the horse manure facing southeast. Third, we began to fill the frame with manure, firmly stomping the manure every 6” until it was about 8” from the top of the frame.

Second, we put the frame together on top of the horse manure facing southeast. Third, we began to fill the frame with manure, firmly stomping the manure every 6” until it was about 8” from the top of the frame.

Fourth, we covered with 6” of soil composted from last years’ frames, and then put the window sash on.

Fourth, we covered with 6” of soil composted from last years’ frames, and then put the window sash on.

Finally, we let the frame set for several days as the manure heated up to 125 degrees. If you plant your seeds right after creating your frame, the temperature will be too hot and you will scald your plants. When the temperature dropped to 85 degrees, I planted the frame and watered it. Sprouts began to appear before the first week was up, and after a few weeks, our hot frame is full of healthy plants on their way to maturity.

Finally, we let the frame set for several days as the manure heated up to 125 degrees. If you plant your seeds right after creating your frame, the temperature will be too hot and you will scald your plants. When the temperature dropped to 85 degrees, I planted the frame and watered it. Sprouts began to appear before the first week was up, and after a few weeks, our hot frame is full of healthy plants on their way to maturity.

The fuels we use to smoke are corn cobs, or “cobs” as they were called in the 19th c. and apple wood. The cobs and apple wood give a sweet smoke. Resinous woods such as pine should never be used as they give an acrid taste to the meat.

The fuels we use to smoke are corn cobs, or “cobs” as they were called in the 19th c. and apple wood. The cobs and apple wood give a sweet smoke. Resinous woods such as pine should never be used as they give an acrid taste to the meat.  The fire will burn low and smoky for several weeks. Each morning the smokehouse will be fired and allowed to smoke during the day. Temperatures in the smokehouse range from 100 degrees to 120 degrees—just warm enough to cure and dry the meat out.

The fire will burn low and smoky for several weeks. Each morning the smokehouse will be fired and allowed to smoke during the day. Temperatures in the smokehouse range from 100 degrees to 120 degrees—just warm enough to cure and dry the meat out.  Check back to see how the smoking goes.

Check back to see how the smoking goes.